The writer Nikolai Nekrasov describes the people found in St. Petersburg. He wrote about this in "Petersburg: The Physiology of a City". However, a visual record of 18th and 19th century Russia provided by Russian artists makes Nekrasov's people more real. The art is not limited to city life. Serfs, the rare freed serfs, and others left the country estates, either legally or otherwise and flocked to cities (with or without internal passports). Some city dwellers left the cities and returned, legally or otherwise (with or without internal passports) back to country estates. Thus city life and the life in the countryside was in continual flux. It is notable that artist Alexei Venetsianov employed linear perspective, as linear perspective was mostly unknown in Russia during the 19th century, unknown even to the Yusupov (<<Юсупов>>) family 1, related by marriage to the Romanovs (<<Романов>>). Let us look at some of this art.

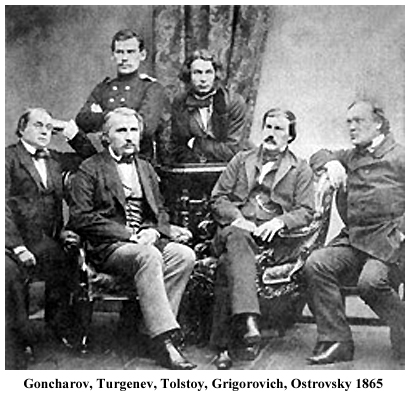

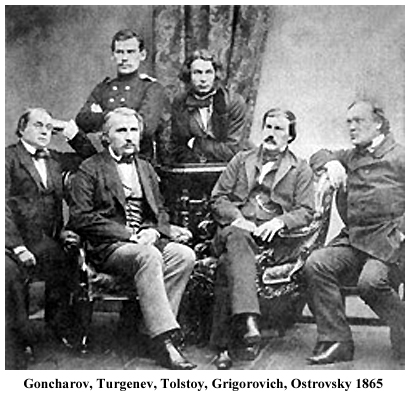

Nikolai Nekrasov was a progressive thinker. He bought the magazine

"Sovremennick" (founded by Pushkin) and printed the works of

writers Goncharov, Turgenev, Tolstoy, Grigorovich, Druzhinin, Ostrovsky.

Nekrasov worked with Belinsky, who highly admired the art of

Schedrovsky: his views of everyday people. The writing of Charles Dickens

was first translated and published in Russia in "Sovremennick". These

thinkers realized that the system of serfs had run its course and was

now historically counterproductive towards building a modern Russia.

It is to be noted that Nicolai Milyutin was very close to Ivan Turgenev,

and was very close to and worked with Mikhail Saltikov (Shchedrin) and

Nicolai Turgenev (a Decembrist) as pioneers in Russian reform. Milyutin,

it might be recalled, advised Tsar Alexander II that a major reason why

Russia lost the Crimean War was a lack of industrial development due to

the backwardness of a society based upon serfdom and a parasitic nobility,

telling the Tsar that it was either reform or revolution. "Sovremennick"

might be viewed as a propaganda arm of the Tsar Alexander II's government

along with the writings of Shchedrin, Tolstoy, Ivan Turgenev, etc. in

bringing about the freeing of the serfs in 1861. Alas, the reforms were not

put in place rapidly enough; the Revolutions of 1905 and 1917 were necessary.

| (English: work) | (Russian) |

|---|---|

| buffoons Click to see | Скоморохи |

| card player | картëжник |

| carpenter | плотник |

| chimney sweep | трубочист |

| coachman (yamshchik) | ямщик |

| cooper (barrel maker) | бондарь |

| degtekurs (distilled tar from birch bark) Click to see | Дёгтекуры |

| factory reader Click to see | Читальщик or Чтец |

| farrier (blacksmith that shoes horses) | кузнец |

| foot porter (podnoschik) | подносчик |

| glazier | стекольщик |

| hook makers | Крючники |

| hunter (ohotnik), example: Sea of Ohotsk (Hunter Sea) | охотник |

| knot tiers (knots for good or evil: pagan) | Наузницы |

| kocar' (kosar', scythe reaper or kosa, not sickle or serp) | косарь |

| lampman (lights/extinguishes street lights) | фонарщик |

| copper smiths | Медники |

| midwife | Повитуха |

| milk vendor, female (molochniza) | молочница |

| mourners Click to see | Плакальщицы |

| nursery governess | бонна |

| oath taker (like a license, a tseloval'nik) See below. | целовальник |

| pastillers (pastry makers) | Пастильщицы |

| peddlers Click to see | Коробейники |

| plevalschiki (turnip seed sower) Click to see | Плевальщики |

| postman (letter carrier) | почтальон |

| pottery maker [possibly using a pottery wheel, in a kiln] | Горшечники [Гончарный круг, in a Печь для обжига глины] |

| Russian Christmas Costume celebration (similar to Halloween) | Ряженые |

| saddle makers or harness makers | Шорники |

| seamstress | швея |

| Seller, apples | продавец, яблоки |

| Seller, bread and cracknel | продавец, хлеб и крекеры |

| Seller, cranberries | продавец, клюква |

| Seller, fish (fishmonger) | продавец, рыба |

| Seller, flowers | продавец, цветы |

| Seller, kvass | продавец, квас |

| Seller, lubok (folkcraft) | продавец, лубок |

| Seller, milk | продавец, молоко |

| Seller, pashka ('tvorog' cheese eaten on Easter) | продавец, пасха |

| Seller, sbiten' (lemonade vendor) | продавец, сбитень |

| Seller, shoes | продавец, обувь |

| street organ grinder | шарманка |

| tavern or inn (kabak, traktir, pogrebok, korchma) 2 | кабак, трактир, погребок, корчма |

| tradeswoman (second hand dealer) | распространительница |

| vagrant | бродяга |

| wash woman | прачка |

| water carrier (female) | водоноска |

| wild bee honey collector | Сборщик дикого пчелиного мёда |

| yard sweeper (janitor, dvornik) | дворник |

During the times of Ivan the Terrible (1530 – 1584), local self-governing

bodies existed called the Zemsky hut (Земская иэба).

It was composed of a Zemzky elder (clerk mayor), the Zemsky sexton

(chanter) and the Tselovalnik: only men that paid taxes and were not serfs,

elected for a year or two. The purpose of the Zemsky hut was to collect

money from the local population (tax farming). As time passed, additional

officers were added such as bailiffs and tax and customs officials. The

duties of these additional officers was to find and punish criminals, and

people feared the Zemsky hut. The honesty of the members of the Zemsky hut

was beyond doubt as the officials, including the Tselovalnik (<<Целовальник>>)

means a "sworn man". Technically, the word tselovalnik is derived from

the contraction of "krestny tselovalnik meaning "the one who

kissed the cross" (swore an oath, terminated by kissing the cross).

After the Polish–Muscovite War and the invasion of the Polish-Lithuanian

Commonwealth (1605–1618), the function of the Zemsky hut evolved: not only

was it required to collect taxes, and punish people, but people could now

be deprived of property if debts were not paid in a timely fashion. Also,

the duties of the Tselovalnik expanded, they became involved in the

business of the Kabak (Tsar's taverns): Kabatsky Tselovalniki were

overseeing tax collection of wine ("razpoy"), beer, and vodka, but were

allowed to sell nuts, berries, pies and pancakes at the Kabak door, to

"pituhi" (drinkers). Drinks were served with a measuring ladel and records

of payment kept. Tsar Mikhail Romanov ordered that no one could establish

a korchma (kabak) near a state kabak. The duties of the Tselovalnik now

expanded to include enforcing that no korchma were near the Tsar's kabak.

To increase kabak profits, skomorokhi (buffoons), gambling, and prostitution

were encouraged in the tsar's kabak.

During the 19th century the Russian state exercised a monopoly on

alcohol, and vodka sellers in taverns were called tselovalniks as

they swore an oath not to dilute vodka supplied by the Russian state

distilleries. As previously stated, these tselovalniks were feared, thus

took advantage of ordinary people, thus the tselovalnik cooper above (see

the art of Schedrovsky) while he may be thought to be "licensed" to guarantee his

workmanship, but the other coopers look away in anger as the tselovalnik acts immorally.

A cooper makes barrels and these barrels hold a stated volume. If the barrels don't

meet standards it would be like diluting what is held in them. Similarly, if

one were to purchase a horse, if the horse had a disease or was lame or was

in some way defective, the horse dealer responsible for the sale, the

tselovalnik would be liable. As time passed, the tselovalnik usually

referred to the innkeeper in the Kabak: the Tsar's tavern. Often these

innkeepers were Jews. Is this not "odd"? Did Jewish "Tselovalniki" kiss

the cross (swear an oath on the Russian Orthodox Bible)? Who would

believe a Jew taking such an oath? No, the Jewish tselovalniki simply

bribed corrupt officials to buy the "title", they swore no oath on the

Russian Orthodox Bible.

Is there evidence that tchinovniki (governmental

officials with a rank (tchin, or чин) could be bribed?

A tchinovnik could easily be bribed. How do we know this? The well known

writer Mikhail Saltykov (Nikolai Shchedrin), or Михайл

Салтыков

(Николай Щедрин)

author of "Tchinovnicks: Sketches of Provincial Life" tells us so. See especially chapter II.

Shchedrin describes Tchinovnicks using bribery, extortion, blackmail, infinite delays (Shchedrin

even mentions Dickens' "Jarndyce v. Jarndyce" in chapter I), secret proceedings,

etc. In the chapter "Times of Yore", Tchinovnicks use torture, violence, even death.

(Click for additional information).

Thus Jews were thought of as predatory, or at best, as predatory agents

of the Tsar.

2

A distinction must be made for words used for a tavern, or pub. A

kabak (кабак) refers to a tavern or

pub where one can drink and get food and is a Russian word. A

Traktir (трактир) refers

to a tavern or pub where one can drink and get food and is a

Russian word. A pogrebok (погребок)

refers to a tavern or pub where one can drink only (no food) and

is a Russian word. A korchma (корчма)

refers to a tavern or pub where one can drink and get food but is

a Ukrainian word.

In a pogrebok (погребок),

one finds "bochki" (бочки) or barrels,

each filled with different wines. People enjoy them selves, smoking

"papirosi" (папиросы)

or hand-rolled cigarettes.

© Copyright 2006 - 2018

The Esther M. Zimmer Lederberg Trust

Website Terms of Use

Website Terms of Use